City Honors and Awards

Step Into a Subterranean Paradise

Discover the breathtaking beauty of one of the New7Wonders of Nature. Glide through an underground river system filled with majestic rock formations and hidden chambers.

8.2 km

Total length of the underground river

4.3 km

Navigable section of the river

1 of 7

New7Wonders of Nature

1999

UNESCO Heritage Site designation

100+

Unique wildlife species

20M+ years

Age of limestone formations

No. 1

Top tourist attraction in Palawan

5★ Rated

Highly reviewed by travelers

Total length of the underground river

Navigable section of the river

New7Wonders of Nature

UNESCO Heritage Site designation

Unique wildlife species

Age of limestone formations

Top tourist attraction in Palawan

Highly reviewed by travelers

PUERTO PRINCESA

CITY TOURISM

Discover the natural beauty, rich culture, and exciting activities of Puerto Princesa. From pristine beaches and the famous Underground River to local cuisine and historical landmarks, find everything you need for an unforgettable visit.

-

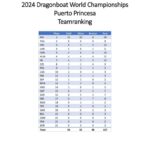

Final Result – 2024 ICF World Dragon Boat Championship November 3, 2024 Puerto Princesa City Baywalk

YPE html PUBLIC “-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.0 Transitional//EN” “http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-html40/loose.dtd”>

-

FOREVER YOUNG BATCH 11

Animnaput anim na mga pundador ng bayan ang kabilang sa Batch 11 ng Forever Young na nakararanas ng pampering mula Nobyembre 10 hanggang 12, 2024. Ang Forever Young ay bahagi ng mapagkalingang programa ni Mayor Lucilo R. Bayron para sa mga senior citizens kung saan bawat barangay sa lungsod ay may isang senior citizen na…

-

TEAM PHILIPPINES, OVER ALL CHAMPION SA GINANAP NA 2024 ICF DRAGON BOAT WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS SA PUERTO PRINCESA

Nagbunga ang pinagsumikapan at pinaghandaan ng koponan ng Pilipinas matapos na masungkit ang titulong over-all champion sa katatapos lamang na 2024 ICF Dragon Boat World Championships na ginanap sa lungsod ng Puerto Princesa mula noong Oktubre 28 hanggang Nobyembre 3. Labing-isang ginto, 20 pilak at 8 tanso ang medalyang nakopo ng Team Philippines. Sa ginanap…

-

SELEBRASYON NG GLOBAL HAND WASHING DAY PUERTO PRINCESA, MASAYA!

“Bakit ang malinis na mga kamay ay mahalaga pa rin” (Why are clean hands still important), ito ang tema ng 2024 Global HandwashingDay kung saan ipinagdiwang ito sa Puerto Princesa sa pamamagitan ng paligsahan sa mga presentasyon ng pinakamahusay na paraan sa paghugas ng mga kamay ng ginampanan ng mga mag-aaral day care centers. Isinagawa…

-

CONGRATULATIONS TO THE NEWLY CROWNED SUBARAW FESTIVAL QUEENS!

SUBARAW Festival Queen 2024- Ma. Ezra Borbon (Cebu City) 1st Runner Up- Rendelle Ann Caraig (Province of Laguna) 2nd Runner Up- Austhrie Sanchez (Vigan City, Ilocos Sur)

-

Barangay Mandaragat, Nangibabaw ang Husay sa Zumbaraw 2024

Sa ikaapat na pagkakataon panalo ang Barangay Mandaragat sa Zumba sa Subaraw o Zumbaraw Dance Competition nitong hapon ng Nobyembre 10, 2024 sa Edward S. Hagedorn Coliseum. Bahagi pa rin ang aktibidad ng Subaraw Biodiversity Festival 2024. Binuo ng 72 miyembro ang grupo na mga babae at lalaki na gumiling, humataw at nagpakita ng pambihirang…

-

June (4th Saturday) — Pista Y Ang Cagueban

The Pista Y Ang Kagueban, a Cuyuno dialect which means “Pista ng Kagubatan” was conceptualized by the then Palawan Integrated Area Development Project Office (PIADPO) in 1991. This is to institutionalize the protection and conservation of the environment for the youth. Irawan watershed was selected as the primary area for the tree planting site. The…

-

February – July — Sports Fair

Puerto Princesa is being frequented by sports enthusiasts nationwide and worldwide to join various sports events. Tagged as the Sports Capital of the Philippines, the City regularly backs world known major sports activities such as basketball, swimming, motocross. This is motivated by its program to preserve its intrinsic magnificence of its environment while sharing it…

-

August – September — Eco-Tourism Adventure

With its fame as one of the worlds’ most gifted cities in terms of environmental wonders, everyone can wander around the Puerto Princesa City and experience the marvelous heaven-made sites crafted by nature and time. Recently picked as one of the New Seven Wonders of Nature, Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park has achieved a…

-

September (3rd Sunday) — Coastal Clean-Up

It is a thorough cleaning and ordering activity to clear up the shorelines. This is an international activity held every third Sunday of September. Its objective is to preserve and safeguard the Mother Earth’s resources along the shorelines. In Puerto Princesa City, it is participated in by government & non-government organizations, barangay officials and its…

-

October – December — Events And Conferences

Puerto Princesa has become the number one pick of planners for big occasions such as summits, trainings/seminars and conferences because of its world-class hotel accommodation, snug and classy restaurants and most of all heavenly-made natural incredulity. All these events are joined in by several groups of fashionable people from all over the country and from…

-

December — Pista Na, Pasko Pa

On the first day of December, the lighting of the giant Christmas tree features the highlight of a month-long celebration of the Holy birth of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Shows and entertainment every night beginning 30th of November are presented by government and non-government organizations, schools, Barangays, Indigenous Peoples, Senior Citizens and all other…